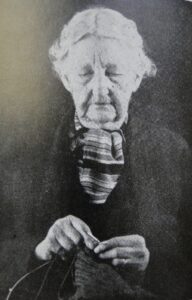

CALM, SERENE, GENTLE

CALM, SERENE, GENTLE

The Story of Susan Miner Johnston

by Mary Lyons Cairns – 1939

A bubbling little woman from Denver visited our club one day. “Isn’t it wonderful,” she enthused, “how one can read a woman’s life in her face? I love to do it and my judgment never fails. That woman over there,” (I followed her glance) “surely has had a care free life, nothing much to worry about, ever…..”

I let her ramble on. After all, what difference did it make? But I knew something of Susan Johnston’s life.

She came to Middle Park in 1879, during the stirring times when we had pioneers. She and her young husband, Tom Johnston, settled first at Hot Sulphur Springs, and then came up to Grand Lake where they built a cabin on the lakeshore near where the Kauffman House now stands. Tom had been there the year before, lured by the tales of vast and sudden wealth to be found in the mountains to the northward. Life looked rosy for them both. Lulu City, Gaskill and Teller had all sprung up like mushrooms. This was the land of promise, where fortunes might be made between the rise and setting of the sun.

Early in the eighties, as the mines proved valueless, one by one, prospectors left for richer fields. But Susan and Tom stayed on. She was to experience all the hardships of the pioneer woman, but to this day none never hears her dwell on the discomforts and privations. “We had lots of good times then,” she will say. Tom was a good carpenter – he would make a living somehow. Game of all kinds and trout were plentiful, even if, at times she had no salt for seasoning. If her supply of sugar failed, she resorted to molasses. In every way she stood the test of those difficult times.

Her son, Robert, was the second white child born at Hot Sulphur Springs, in 1880. In 1881 Willard (or Wid) was born at Grand Lake, the second white child born there. He was followed by Jim, Johnnie and Marjorie, all without benefit of doctors or trained nurses, or a wisp of ether to ease the pain. When the children were little Tom took up a homestead on Stillwater Creek and the hardships began all over again.

An occasional dance was the only recreation that the region afforded. At these times they bundled up the babies and went, sometimes miles and miles away. The dances would begin at seven o’clock and would last until morning. On these rare occasions all the pleasure possible must be crowded into a few brief hours. Old Uncle John Mitchell, high on the platform, played his fiddle joyfully, and when he called the square dances he did it with great gusto.

In the intervals there was work; babies and work, work and babies. But when a neighbor needed help Susan was the first to go, sometimes riding horseback on a side saddle with her smallest child tucked on in front.

It seemed no time at all until the children were almost grown. She had worried a little about their schooling; four months each year seemed to be all that the district could manage, and she knew that had to be inadequate. To supplement this meager education she had the teachers stay in her home, knowing that the children would absorb much from the association. Most of these girls were far from home, and she recognized this fact and mothered them lovingly. There was Margaret Haughwout, a girl of brilliant mind, who afterward published “Sheep’s Clothing” and other poems; and Lola Gebhardt, whose musical talent now stood her in good stead, for she never seemed to tire of accompanying Jim and Johnnie on the piano while they wrested music from their violins. These teachers and many others gave of themselves to the Johnston children – grown and growing – but in return Susan Johnston gave back to them something that was priceless.

Year after year she took boys and young men under her wing. The Smith twins – Henry and Preston – whose mother was dead and who needed a home; Ed, their younger brother; Fred Maker, Tay Lehmkuhl, Chester Bunte, Jack Joslin, Howard Beehler – the list could go on and on.

“You’ll go bankrupt,” some of her cynical neighbors told her; “you can’t afford to keep everybody for nothing.”

“They pay,” she answered calmly. “They pay in more ways than one.”

Tourists began coming into the Stillwater country in great numbers for the fishing. They wanted the Johnstons to build a bigger house so they could be accommodated. It meant borrowing money, but Tom’s ability as a carpenter made the building possible. He built a big house on the ranch, and then…

Josephine Langley tells about it in this way: “One evening I went from my hotel over town to the post office. A storm came up, but when I got home the moon was shining. I went in the lobby. It was dark except where the moon shone uncannily on the furniture. Just as I was about to strike a light, a voice called, “Hello, there Josie!’ I lit the lamp and there was no one in the room. Always before death someone calls me that way. The next day Tom Johnston died.”

But Susan had no such warning. The shock of Tom’s going crushed her for a time, and the way ahead seemed long and lonely. Then she put her grief aside. “The children still need me,” she said bravely, and with that thought she carried on.

A few years before this Wid had gone away. Wanderlust had claimed him, and he was jockeying down south, going from city to city and from one race track to another. His letters came but seldom, and then cased altogether. “If he would only write,” she’d whisper to herself with longing far too deep for many words. “Just a line or two at Christmas,” she prayed. But years went on in silence.

Preston Smith was the first of the boys whom death took from her. An expert horseman, he was breaking a bronco on the ranch when it threw him and killed him instantly.

Rob went up into Wyoming, married and came home two years later with his motherless baby boy. Susan took little Tommy in and cared for him through his babyhood and young childhood.

Then came the World War. Johnnie, her own boy and most of those she had mothered, went into the service. Her hands were busy for them all, and her heart was with Johnnie and Fred and Chester and all the rest – at the front lines in France, in camps at the west coast, and at the east; the uncertainty, the months of waiting were almost unbearable.

But at last they all came home. It seemed unbelievable, but one by one they all returned to her own roof again. Fred had been badly wounded overseas. None of the others were injured, except as war brings changes to all men.

And then the aftermath! That terrible influenza epidemic penetrated her beautiful mountain country, and one after another of her boys were stricken. Allen Murdock, Marjorie’s young husband, went all too quickly, leaving Marjorie and her baby boy to come home to Stillwater ranch. “Poor, poor little Margy,” Susan cried; “and Allen was so fine a fellow!” Next to go was Henry Smith – good dependable Henry, whose life was snuffed out overnight; and in a day or two his brother Ed was gone. She was busy every minute, going here and there, nursing, comforting, caring for the loved ones, healing sorrows of those who were left. Her own heart was breaking, but she found time to help them all.

Other tragedies came thick and fast, with only here and there a ray of sunshine. Cattle thieves were stealing and butchering the Johnston calves, mutilating the brands so that even when the hides were found it was difficult to prove their ownership. Rob and Jim conceived a plan to lie in hiding and catch the culprits. On a dark night they crept stealthily to where they felt the thieves would come, then separated a short distance to watch for any strange approach. There was a sudden swaying of bushes and Rob fired straight up into the air. He ran to identify the cattle thief. There lay his brother Jim, the victim of a bullet which had glanced against a tree limb.

They opened the Community House in Grand Lake for Jim’s funeral; Jim – young, happy, care-free Jim, who had given unstintingly of his time and strength to work on that building, little dreaming with each stroke of his hammer he was building a lasting monument to himself.

Even that day Mother Johnston did not give way to uncontrolled sorrow. “Poor Rob,” she said to sympathizing friends, “it is Rob who needs your words of comfort most.”

One day word came that someone had seen Wid far down in Texas. Maybe he had had enough of wandering. If only he would come home, or write! Johnnie, now in the Forest Service, heard this. As soon as he could get leave he put his mother in his car and together they drove down and brought Wid home. The lost was found, and her mother heart was glad. “Rejoice with me! I have found my sheep which was lost.”

She sold the ranch and went to live in Grand Lake village where Rob and Wid and her brother Frank built her a comfortable home. “It must have a couple of extra rooms,” she said. “Some of my boys and girls (and I mean all of them, not just those who are related to me) will come to see me as the years go by.”

A few years before this Marjorie had married Albert Penney, and they, with young Allen and their own two children, lived on a nearby ranch. Al Penney was like Mother Johnston’s own son, and she came to depend upon him for his unerring advice and counsel.

Perhaps now life was to hold for her only comfort and peace. She told herself that she was growing old when she counted the years, but she didn’t feel old, really.

Then Rob’s wife, Helen, became almost helpless with arthritis, and there were six young children who needed care. “I’ll do my best to help them,” smiled Mother Johnston. Her best was wonderful indeed.

Death came to her loved ones after this, not once but many times. It took her brothers, Willard and Frank; then two beloved sisters, Mary and Lucy. Each passing brought deep sadness, but she would not let grief overwhelm her. “Their families feel it more,” she said, and straightway went about helping them all she could.

But when Johnnie’s little Patsy was taken away and he and Buelah, his wife, brought the tiny form home to Grand Lake for burial, her courage almost failed. “So sweet a child,” she murmured. “They fairly worshipped her. I wonder why she had to go.”

She wondered why again when Marjorie and Al Penney lost their home by fire. “They loved their home,” she pondered. “I wonder why it had to go. They’re all so good; I just can’t understand it!” Later the Penneys built another home and everything seemed going smoothly, but just a few months later—

“I miss Al so,” said Mother Johnston quietly. “He was so dependable. But I mustn’t feel sad for myself. Poor little Marjorie is so brave. She has a quality of courage and a spirit I’m sure I never had. She is dry eyed; says she must stay on the ranch, for her work is there. When Al was stricken with that heart attack Margy was desperately and tragically alone. She sent Martha and Frank for help, through that terribly deep snow. She worked over him, trying her best to keep him alive even after she knew he had stopped breathing. And then—can’t you see her little figure walking out alone to meet the children so that they wouldn’t come into the house unprepared for what was there?”

I glance across the room at Mother Johnston as she stood there with the other women of our village repeating the club collect, her face alight, her blue eyes shining: “Make us to grow calm, serene, gentle.” I could not say the words, a lump in my throat was choking me. In my heart I whispered fervently “AMEN!”

SUSIE’S STORY

by Buelah Johnston, 1930

“I have heard that lives go in cycles. If that is true mine has been completed as it was just fifty years ago this summer that I came here as a bride and now I am back,, building a new home here. Fifty years and the lake looks just the same.” The gray haired woman who was Mother Johnston to half the county ended her remark softly as we sat upon a granite boulder among the pines and looked out across the rippling, sun-flecked water one summer day.

“Tom had a three room cabin ready for us on the point by the inlet. It was built over long ago and since added to until it is now that big house with the tall chimneys you can see above the trees. But they kept the original cabin, it was firm and sturdily built,” she added pridefully.

“Your little cabin was very much like you, wasn’t it, Susie dear?” As she looked at me in surprise I continued, “Life has changed you outwardly too, since those happy days on the Point but like the sunny little house your standards have stood firm – but do not listen to me. I want to hear about when you lived here.”

Mother Johnston continued, “There weren’t many people right in the town then – no summer people at all of course, but just let someone give a dance, or election come and it seemed that out of every gulch poured men. Old, young, good and bad, alike in one thing only and that was their desire for gold.

Our first summer was all play. I tagged after Tom wherever he went. While he tapped rocks here, there and everywhere with his prospecting hammer I fished the swift little streams, gathered wild berries or hunted grouse with the twenty-two rifle he had given me soon after we were married.

Then our babies came, first Robert, then Willard – quite close together, but they were such good little boys and played so well together. I can still see them sitting as still as mice in one end of an old water-soaked row boat while I rowed out into deep water, dropped anchor and fished for half an hour. I think fishing must have been better then than now, I never had any trouble in getting enough for our dinner in that time, and now I see boats stay out half a day.”

“Or perhaps you were a better fisherman,” I suggested.

“It was the summer Wid, as Rob called him, was two that Father Monmartin came and the men of the community built the Catholic Mission. It was good to feel we had a church, tho not many went. You get out of the way of churches off here in the mountains, tho I don’t think you get away from God.

It was on the morning of the Fourth of July of that year – your Aunt Molly was helping me get a big dinner. All the relatives from Hot Sulphur Springs were coming and of course any friends that might be in town would be there. There was to be speech making and foot races on the lake shore and fireworks in the evening. It was to be Grand Lake’s first celebration so everybody was full of high spirits. Everyone who had a flag had it out and I remember the little frame building they used for the court house had bunting all along the porch rail.

I was cutting up chicken when three shots rang out, in a minute, three more – then one. Molly laughed and said, ‘The fireworks are starting early.’ It was just a few minutes until Tom came running in, white as a sheet and cried, ‘My God, Susie, they’ve killed the Commissioners! Shot them from ambush on the trail along the west side of the lake!’ and he grabbed his rifle from the rack and ran out.”

“But Susie,” I gasped, “Why would anyone do a thing like that?” Mother Johnston explained, “Some thought the seat should be moved to Hot Sulphur, which it was later, but bitter feeling started and one thing led to another until that wicked deed was done. One of the ambushers was killed when the Commissioners returned there fire, and many were suspected. Two were brought to trial – one of them was later your Uncle Lon Coffin. He was held in jail in Georgetown. We all went over for the trial, but,” with a chuckle, “I could establish an alibi for him easily enough. He had been on the back porch pestering Molly most of the morning when I wanted her to help me, and had left such a short time before the shooting that he couldn’t possibly have got clear around the lake. As soon as he was freed he and Molly were married and we all returned to the Lake as gay as could be.

We went back to Kansas soon after that and stayed for thirteen years, as long as Tom’s mother lived. Jim, Johnnie and Margie were born there.

“Did you like it better there?” I asked.

Susie smiled, “No, we tried to be patient, but Colorado and it’s mountains were always calling us, and as soon as his Mother was laid to rest Tom hurried back to join Lon in another gold mining venture – the one that was to make us rich.

As soon as they were outfitted and ready to start into the hills Tom wrote me to sell everything and get ready to come. It took me all summer to straighten up everything.” An amused laugh rose to Susie’s lips as she recalled the memory of that journey.

“Even as much as children like to eat on the train, there was plenty of fried chicken to last throughout the trip,” she said. “Every friend and neighbor in that little town appeared at the station with a box lunch for us and – they all had chicken.

I never did willfully deceive anyone before, but I did the railway company.” Then in an apologetic tone, “I had so little money and so many needs. Widdie had never grown as he should and although he was fifteen he was no taller than ten year old Jim, so I dressed them just alike in knee pants and ruffled shirts and bought a half fare ticket for him.” With a rueful smile, “I thought I was caught when I overheard him telling the conductor about riding race horses but he thought it was only childish bragging.” Then with a sigh, “He had the fever of the race track in him even then.”

“It was just like taking care of a covey of mountain grouse, trying to watch those four boys the morning we spent in Georgetown waiting for the stage to Hot Sulphur Springs. Georgetown is a pretty little place set deep in the gulch with bare mountain sides going almost to timberline on three sides of it; all of the hillsides were gophered with prospect holes. I would just get two of the boys within calling distance when the other two were off, scrambling up the slopes to peer into another abandoned hole.

The trip over the range was another test of nerves. The road was only wide enough for one vehicle with turnouts every half mile and so narrow that it had to be cribbed up in places. The boys were so anxious to see everything that they were half out of the coach most of the time. I am sure my cries of ‘Jim, do sit down’, ‘Johnnie, be careful’, and ‘Rob, you must watch the little ones’, must have rung in the driver’s ears for many days.

My friends and sister, Lucy, and her family in Hot Sulphur Springs tried to persuade me to stay there that winter and let the men go on to Whiskey Park alone, but,” with a smile of sweet remembrance, “Tom wanted us with him and of course that was where I wanted to be.

We made quite a procession; four big freight wagons loaded with tools and equipment; Molly, Lon and their three children, for, (Molly said if I went she would too) in their wagon; Tom, the little children and I in one wagon; Rob, who thought he was old enough to do a man’s work, driving one team and Jim McBride, the third partner in the mine making the fourth.

We camped the first night at a ranch on the Troublesome. The next morning Jim crept out with a small rifle, sure that we were in the wilds and when one of the rancher’s Plymouth Rock hens appeared through the willows he promptly shot it and hurried back to camp to display his prairie chicken.

After days of jiggling and bouncing over roads none too well cared for to begin with and which grew worse each day, the crude cabins and stables which the men had built during the summer were a welcome sight to men and beast alike. The rolling hills surrounding us were dotted here and there with patches of spruce and aspen. The latter’s leaves touched by the early frost were as bright a gold as we hoped to find at their roots.

The Elkhorn mine which held such rich promise proved to be a rich pocket only seventy-five feet in depth, but by the time this was learned a brilliant offer for it had been refused and the snow was three feet deep so we had to stay on until spring.

It grew tiresome, so few people and mail not more than once a month when one of the men would snowshoe fourteen miles to Columbine, but we suffered no actual hardships. Of food, there was plenty but no variety. Molly and I racked our brains trying to devise new ways ofcookinig dried fruit, beans and bacon.

Toward spring our meat supply ran low and the men in camp snowshoed out to some barren ridges to the south where deer were wintering and shot two bucks. I shall never forget that meat. Due to the hard winter the deer were thin. I used to boil that meat all day and still the boys would say they could not stick a fork in the gravy.

The children had a pet doe that followed them everywhere just like a dog. She wore a piece of red flannel around her neck so hunters would know her. We had to watch her on wash day as she loved to play with the clothes on the line and with her tiny sharp hoofs she would rip a garment to ribbons.

The men had all allowed their beards to grow all winter as a protection against snow burn. One day toward spring Tom decided to shave and after doing so found that he scarcely knew himself so he put on his black suit and slipped down to Molly’s house and had her send out work that there was a stranger there who was interested in buying the mine. My! Such scurrying around and how importantly the men all walked and talked to this strange man who kept back a little in the shadows until he couldn’t keep on any longer without laughing.

That was our last attempt at mining. As early as the roads would permit we loaded our wagons, took our glass windows out of our cabins and made the long hard trip back to Middle Park. There we bought the Stillwater ranch but as it had no house on it, only a two room cabin right down in the creek bottom among the willows, we went on with the Coffins to the adjoining ranch which Lon had owned for some time. But the house was dark and odorous from being empty so long and made dark and gloomy by so many pine trees being so close about it, and the two families of children had been together for so long that quarrels started for no reason at all.

I was very unhappy and for the first time felt homeless. The men were away cutting wild hay wherever they could find it to feed to the stock through the coming winter. One day the children and I walked over to the little cabin in the willows. It looked so cheerful and sunny that I swept it out with an old worn out broom which I found in a corner and calling the boys, I said, ‘Come on, we are going over to Aunt Molly’s and get our things. We are coming home.’

Molly cried and begged us not to leave and imagined all sorts of wild animals creeping around at night, but I was determined so we loaded up our precious windows, and while they were much too large for the openings we nailed them on the outside and they served very well. We had an open fireplace to cook by. I will always remember the brightness of the sunshine as it poured into our doorway those late summer mornings.

There is lots of work attached to making a hay ranch out of a sagebrush flat. The boys, especially Jim and Johnnie were so little to grub sage and all the other hard work that seemed their share, but,” brightening at happier memories, “They had lots of pleasures, too.

Margie was so small when we first went to Stillwater that I used to worry that she would get lost. She wandered so far hunting flowers in the sage brush. But we had an old shepherd dog that was her constant companion. I would see her bonnet and his curved-bushy tail over the high sage and then I would know she was all right.

One spring morning Jim and Johnnie were busy out at the shop fixing a set of harness for a team of burros a prospector had left at the ranch. About ten o’clock they drove up to the gate in a rickety old buggy and called me to come take a ride. I said, ‘All right, but I can’t be gone long or dinner will be late.’

Jim said, ‘Oh, we will get you back in time,’ with a look at Johnnie at which they both giggled. ‘Here, you sit with Johnnie, I will sit in the back.’

I was no sooner seated that the burros pricked up their ears and trotted off, as smartly as our best driving team. We took a fine ride with the burros keeping up a brisk trot all the way and it was not until we returned home, when, in getting out, I tripped over a wire, that I found those boys had a wire connected with the burros bits and attached to a telephone generator which Jim had been grinding merrily all the while. Those poor burros surely were shocked into action.

I think we had the most fun of our lives at Stillwater. Jim and Johnnie began playing for dances when they were still very young and rather than let them go alone we took them. I guess that got us started. We never thought of missing a dance anywhere from Coulter to Hot Sulphur Springs. One winter night, I think it was New Years, we went to Lehmans. We danced until midnight and then had a big supper, everyone had brought things of course, and Mrs. Lehman made a wash boiler full of coffee. Then after supper it got so cold we couldn’t go home, so we danced on until morning and Mr. Lehman, himself, cooked breakfast for the whole crowd.”

“Were you quite popular, Susie?”

“Of course I was. I was a good dancer,” she declared with spirit.

“I expect you were pretty too,” I suggested.

“I may have been,” she said modestly. “No one ever told me so but once and then Tom took me home before the dance was half over.”

“Why, Susie, did you have an admirer?”

Top thought so. It was just a young easterner out here to make his fortune in a year. He wondered how any girl as pretty as I could belong out here. I expect men are still saying that to western girls – but that was long before I had boys big enough to play for dances.

Wid was the only dissatisfied one of the children and he was always longing for the race track. All his talk was of riding and he was little enough to be a jockey. I used to wish he would grow up suddenly and thick maybe it would change his mind about what he wanted, but he didn’t and at last he decided to go. His father and I wouldn’t keep him, knowing that he felt as he did, tho we did need him on the ranch. The younger boys weren’t very large to do all the work we had to ask of them.

Twenty five years ago last spring he left and five years since I had a letter from him.” Then with a tiny sigh, “He is never far from my thoughts.”

The Mickey – a big, new pleasure boat chugged past, making the waves lap higher on the rocks on which we sat. My outward eye saw and registered this fact but at heart I was back at Stillwater watching Susie’s family grow up, enjoying with them their music and their pranks and suffering with them their heartaches and disappointments.

“It wasn’t long until Rob went to Wyoming to visit Aunt Molly and was married there. It was just a year later that he and Aunt Molly brought his tiny motherless son home to raise. He was such a comfort to us, particularly as we had to lose big Tom in such a short while. I thought for while I couldn’t stay on where everything I saw and everything I touched reminded me of him, but nothing is ever gained by running from sorrow. Soon I began to love more the very things that had hurt me so at first.

Tommy was such a little mite, I was always trying to fatten him up. Once I gave him too much cream in his bottle and made him sick and he drank skimmed milk ever after. Of course, he as teased and made much of by all our boys and all the other big boys who were always there. Once Rob came upon him sitting in the sun at the south end of the Post Office, holding a kitten. He would spank it sharply, then hold it to his ear and listen and spank again. Finally, he said ‘Boil, damn you, boil.’

Each of my children have had a measure of happiness, even Jim who was taken right in the prime of life, which always seems the hardest. Each, too, had had to face that most severest of trials – the loss of a loved one, but they have all stood their tests with courage. It was from their Irish father, I think, that they learned to meet life with a smile and a joke on their lips.

Tho we have never been a family to talk much of religion, I know that they all have a deep abiding faith as I do, that we are simply carrying on here as best we can until we can all be together again.

The ranch was too much for me after Johnnie married and went away. It became so run down that I knew Tom wouldn’t be proud of it, so I was glad to sell. I am glad too, to have a house here at the Lake close to Rob and his family – but you see why I say I have lived my life in a circle and am back at the starting point.”

As we rose I realized that the sun had set and the soft twilight was already settling over the lake.

With all apologies for not making a better story from such good material.

Buelah