Who Was Louise Millinger

“Grand Lake’s Best Known Woman”

Louise Millinger

From 1933 through 1954 Grand Lake summers were graced by a “one woman Chamber of Commerce”. This unique character was Louise Millinger, operator of the Grand Lake Boat Service.

The Boat Service was started by her father, Captain McCarty, in 1909 with some canoes and one cylinder motorboats for the “wagon trade”. Louise and her husband Clem took over the business after the Captain’s death in 1933. Clem died suddenly two years later, and Louise, at age 49, continued doing what she loved. She spent her winters teaching at Minnequa school in Pueblo and writing fiction. From the day school was out until the day it started in the fall, Louise was with her boats. She built the operation to six Chris Crafts, a 40′ steamboat “Micky”, and many small boats and canoes. She had shops capable of total motor rebuilding, and a heated and insulated hull refinishing shop. Her marina also included storage facilities, employee housing and an office.

When her lake shore clients wanted a new boat, they sent her to the factory to select the craft, have it transported and prepare it for launch. When the owners of Daven Haven Lodge ordered “Lady of the Lake”, she was told by the factory representatives twin engine craft would never be required on a small lake. After an education from Louise about the effects of altitude on internal combustion engines, however, Chris Craft knew they had met their metch.

Few boats ever left Grand Lake in those days. When a boat’s useful life was over, it would be laden with pine boughs, saturated with gasoline, towed to mid-lake and ignited.

Mrs. Millinger continued a tradition started by her father. Vesper services were held on the lake shore every Sunday evening during the summer. She would have a large bonfire on the beach. These services were nondenominational. Louise would have a piano loaded onto a truck and brought to the beach for music, and often the bell ringers would also play. The services would close with a trumpet soloist from across the lake playing taps.

Louise was a Director of the American Power Boat Association, and a popular public speaker for the association. She always urged people to visit Grand Lake, and “See the Top of the World from a Boat”. With her hectic work life, one of her favorite things to do was paddle out to a special spot on Grand Lake and just be still.

In 1948, Ralph C. Taylor wrote in Rocky Mountain Empire magazine, “Louise Millinger gathered as much fame in one generation as the lake did in 6 million years.” Louise died in March 1985 at age 99. The “Lady of the Lake” lives on to this day, winning prizes in antique boat contests.

Meet Grand Lake’s Petticoat Commodore

By Ralph C. Taylor

Special Contributor in the Rocky Mountain Empire Magazine.

Grand Lake, Colo.

(Rocky Mountain Empire Magazine, Sunday, September 14, 1947)

Uncle Sam wasn’t exactly original during the recent war when he gave his navy the feminine touch. Thirteen years ago a woman too command of the unique Grand lake fleet that plies the sky-blue waters of this picturesque high-altitude Colorado lake. Certainly no other “navy” has a petticoat commodore.

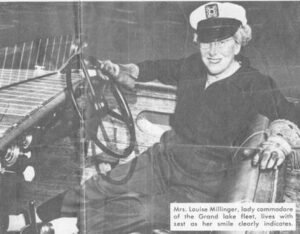

She is Mrs. Louise Millinger, who sails on the top of America as a sight-seeing world gone by. Despite her modesty, she has gathered about as much fame in one generation as the lake has in 6 million years.

For thirty-eight years she and her family have been unofficial custodians of Grand Lake. Her father operated the boat service originally and Mrs. Millinger had no notion about becoming an inland sea captain. She was a primary teacher in Minnequa school in Pueblo. It was fourteen years ago that her father died. Mrs. Millinger’s husband, Clem, took over, but two years later he passed away and the boat service became Mrs. Millinger’s, with a challenge to carry on the tradition of Grand Lake.

In the years she has been in charge, Mrs. Millinger has blossomed into a one-woman chamber of commerce, vivacious hostess to hordes of the nation’s big names, and protector for thousands of run-of-the-mill tourists.

Mrs. Millinger, however, would have everyone forget that she is a woman. She would rather talk about new ways of providing comfort, pleasure and safety for the thousands who each season accept her invitation to “See the top of the world from a boat.”

To understand her great devotion to Grand Lake the newcomer must realize that nature went to work some 7 million years ago by maneuvering glaciers among the 14,000 foot peaks to smooth out the bed for this mirror of the heavens and make it the source of the great Colorado river.

This lake is one part of America that the white man did not take from the Indians. Why they abandoned it is one of the rich old legends that about at Grand Lake.

Long before Columbus, says the story, Arapahoes and Cheyennes joined forces to expel the Piutes from the lake country.

After three days on the warpath, even the Utes realized their doom. Hoping to take their women and children to safety across the lake, they built a large raft. That night as the refugees neared the center of the lake a fierce storm churned the waters and the lake swallowed the raftload of screaming squaws and papooses.

On shore, the braves who managed to escape the ruthless Arapahoes and Cheyennes said that the evil spirit that lived on Shadow mountain had wrought the tragedy. They never returned to Grand Lake.

The mist that rises each morning from the water and clings to the mountains, the Utes said is the spirit of their drowned families pleading with the evil spirit for restoration of life.

This story also haunted the Arapahoes and Cheyennes until they also feared the evil spirit. Every time they started across the lake in canoes they felt the pull of Shadow mountain. As they paddled closer to the shadow of the mountain the shadow withdrew, as if taunting them and coaxing them toward disaster.

Ninety years ago Chief Colorow, seeking to drive the white man and the evil spirit out of the hunting grounds, wrote the Indians’ finish in the area by setting fire to the grass. The wind changed quickly and ruined the region for decades.

It was in 1909 that Mrs. Millinger’s father, the beloved Capt. W. J. McCarty, put some one cylinder motorboats and canoes on Grand Lake for the “wagon trade” that came over the steep, winding stage roads. Mrs. Millinger and her husband spent many summers helping run the boat concession. It was summer fun and a pleasant hobby.

After Captain McCarty died in 1933 she regarded it as a family tradition entrusted to her. So she learned the business from sea level up – from boat factory to Grand Lake mooring. She watched craftsmen build motors and shells; she asked thousands of questions. Now, probably she knows as much about motorboats as any woman, but her studying and questioning go right on.

Boat Service in the Rockies

The pride of her business is the complete boat service high up in the Rockies. There are elaborate shops where motors are rebuilt completely. There is an insulated paint room with special window and electric lighting, where boat hulls can be heated while being refinished.

Mrs. Millinger and her “boys” have built a confidence among the boat owners so enduring that at the close of each season the summer colonists give Mrs. Millinger the keys to their boats, with blanket orders to give them whatever care they need to put them in top shape for the following season.

When the wealthy residents who own homes around the lake get ready to buy new boats, they often send Mrs. Millinger to the factory to select the craft, have it transported to the lake and prepared for use. She is a full fledged agent for boats and water craft.

Once a boat is launched on Grand Lake it seldom leaves. It is not too easy to get them in, because they must be hauled by trailer over the Trail Ridge road or Berthoud pass. When a boat has served its time, it becomes its own funeral pyre. Laden with pine boughs and saturated with gasoline, the retired boat is towed to mid-lake and ignited. The boat colony gathers around until the flames eat to the water line and the craft slips to the lake bottom.

Grand lake, at 8,369 feet above sea level, is the world’s highest yacht anchorage. Each August sailboats are brought in from distant points to compete in a week of regattas. Sir Thomas Lipton, although never a visitor to the lake, furnished the cup for the regatta winner.

Sails Against the Mountain

The white canvases spread to the alpine winds against the background of Shadow mountain is a colorful and picturesque sight, something that inlanders travel hundreds of miles to see each season.

Sailboats take most of the regatta week spotlight, but the motor races come in for spectacular dashes. Last August Mrs. Millinger won the speedboat cup with one of her boats.

The trophy joined Bing, her canine companion and bodyguard, as among her prized possessions.

But she doesn’t go in much for speed. First consideration for everyone on the lake, whether in one of her boats or their own, is safety. The Millinger boats patrol the waters constantly and each season several persons are pulled from the lake when private craft capsize.

In almost forty years not a life has been lost in her flotilla of speedboats, rowboats, canoes and Mickey, the twenty-passenger boat that is favored by many lake visitors.

If necessary, she responds alone to a call for help. Her boats are moored so that they can be untied by one jerk on the rope. The rescue pattern is to drive reasonably close to the victim, toss out a rope or life preserver, cut off the motor and let the victim made his way to the side of the boat. Not until he has his hands on the craft is he given other help, otherwise he might pull the rescuer into the lake – and its bottom in spots never has been sounded.

Mrs. Millinger’s hobby, when she has time in the winter months in Pueblo, is writing fiction. Many of the plots she catalogs in her mind as she watches and listens during the summer.

Continues Vespers at Lake

Her super abundance of energy expresses itself through membership in the Pueblo Altrusa club, of which she is past president, and the Pueblo Writers club.

She gets extreme satisfaction in perpetuating the Sunday evening vespers which her father started long ago along the shore when visitors found Sundays hanging heavily. The nondenominational gatherings around a campfire has become the highlight of each week.

But often, Mrs. Millinger likes to paddle out to a special spot in the lake in the evening and just sit still.